What does it mean to be bilingual? Understanding True Fluency

You know how the label “bilingual” can feel like a moving target in a bilingual community, especially if you can chat comfortably but still freeze in a meeting or miss jokes.

In real life, “true fluency” is less about sounding like native speakers all the time and more about using two languages to get things done across the situations that actually matter to you.

This guide clears up the native-speaker myth, explains how bilingual education and the mother tongue shape language learning, and shows you how to use practical tools like a bilingual dictionary, IPA notes, and a few core linguistics ideas (including universal grammar) without getting lost in theory.

Read on.

Key Takeaways

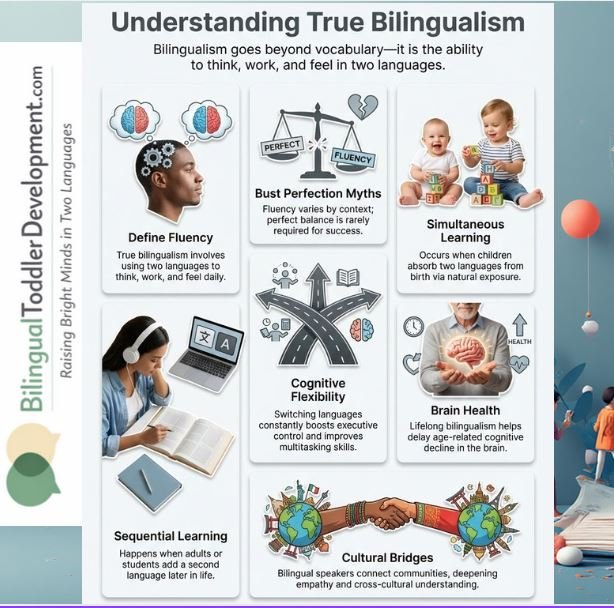

- Merriam-Webster (accessed Jan 19, 2026) defines bilingual as using or being able to use two languages, especially with equal fluency.

- Balanced fluency is functional balance, not perfection. You can be stronger in one language by topic, setting, or skill (speaking vs. writing) and still be bilingual.

- Bilingualism develops through simultaneous exposure (two languages early) or sequential acquisition (a second language later through school, work, or bilingual education).

- Cognitive benefits are real but nuanced. The most reliable gains show up when you use both languages regularly, including switching on purpose instead of avoiding harder contexts.

- A bilingual dictionary helps most when you use it for part of speech, usage notes, and pronunciation (IPA), not just one-word translations.

Defining Bilingualism in a Bilingual Community

True bilingualism means you can use two languages to think, work, and connect with people. That does not require “perfect” grammar or a flawless accent.

In the U.S., bilingualism is common enough that you can build a real daily routine around it. A U.S. Census Bureau release on 2018 to 2022 American Community Survey estimates reported that 78.3% of people age 5 and older spoke only English at home, which means millions of households operate in more than one language.

What most people miss is this: bilingual ability is often “domain-based.” You might handle family life in your mother tongue, but prefer your second language for work email or school vocabulary.

- Use: Can you do real tasks (schedule, explain, persuade) in both languages?

- Range: Do you use both languages across more than one context (home, work, school, community)?

- Stability: Can you keep it up without translating in your head for every sentence?

- Repair: When you get stuck, can you rephrase, clarify, and keep the conversation moving?

What does it mean to be truly bilingual?

A person who is truly bilingual can use two languages with fluency. That matches the everyday dictionary meaning: you can operate in both languages, not just recognize a few phrases.

The “equal fluency” part is where people get anxious. In practice, you can be bilingual and still have gaps. Most bilingual people do, including multilingual people who switch languages depending on who they are with and what they are doing.

If you want a grounded way to describe your speaking level, the ACTFL Oral Proficiency Interview (OPI) is widely used in U.S. academic and professional settings and focuses on spontaneous, real-life speaking. It is a helpful reality check if you are tired of guessing where you stand.

Fluency lives in use, not in tests.

One pro-tip: stop measuring yourself against an imaginary “native speaker” version of you. Instead, measure whether you can handle the situations you care about, like a parent-teacher conference, a customer call, or a full weekend with relatives.

The concept of balanced fluency

Balanced fluency means you can use both languages with similar ease across the contexts you actually live in. It does not mean you have identical vocabulary in both languages.

This is where the grammar details matter. A good bilingual dictionary can show part of speech (noun, verb, adjective), common collocations, and usage notes so you pick the word that fits the sentence you are trying to build.

| Profile | What it looks like day to day | How to build balance |

|---|---|---|

| Balanced bilingual | You can work, socialize, and handle logistics in both languages with minimal strain. | Rotate “high-stakes” tasks (calls, meetings, school forms) between languages. |

| Dominant bilingual | You feel fluent, but one language carries most of your complex thinking. | Pick two domains you will “upgrade” in the weaker language (work topics, healthcare, parenting). |

| Receptive bilingual | You understand well, but speaking or writing feels slow. | Use short daily output: voice notes, summaries, and 5-minute conversations. |

If your pronunciation is the friction point, use the IPA line in your dictionary entry. Focus on stress marks and the one or two sounds that change meaning most (like vowel length or the difference between a “b” and “v” sound in some accents).

How Bilingualism Develops

Bilingual children may acquire two languages early or build a second language later. Adults can also become bilingual through work, relocation, or structured language learning.

The path matters because it changes what feels effortless. Simultaneous learners often sound natural early, but still need literacy support. Sequential learners often read and write well, but may avoid fast, informal conversation unless they practice it on purpose.

The American Speech-Language-Hearing Association explains that using more than one language with your child does not cause or worsen speech and language problems. In fact, a strong foundation in one language supports additional language learning.

Simultaneous vs. sequential language acquisition

Children can pick up two languages at once. Adults can learn a second language later in life.

- Simultaneous exposure means a child hears two languages from birth or very early childhood, often at home and in a bilingual neighborhood. To support it, give each language a consistent “job,” like bedtime stories in the mother tongue and school routines in English.

- Sequential acquisition starts when a person adds a second language after the first, often through school, work, or a bilingual education program. Expect uneven growth at first. Listening often leads, then speaking, then reading and writing.

- Family routines shape outcomes. If you want your child to keep the home language, protect it with predictable time blocks, like dinner conversation, weekend activities, or calls with grandparents.

- Use tools that force sentence-building. Flashcards help, but they can trap you in single-word thinking. Add example sentences, swap the subject, change the tense, and track how the part of speech changes meaning.

- Practice across contexts. Many learners feel “fluent” in class but stuck at the doctor or at work. Create a short list of scripts for your high-frequency situations, then rehearse them out loud until they feel automatic.

- Document what you can do. If you list bilingual skills on a resume, tie them to tasks (client support, translation, presentations) and be clear about your strongest skill areas (speaking, reading, writing).

The Cognitive and Social Benefits of Bilingualism

Learning a second language can sharpen attention, improve communication across cultures, and strengthen cultural identity. You also gain practical flexibility inside a bilingual community, like helping family members, mentoring new arrivals, or serving customers more effectively.

The benefits show up most when you keep both languages active. If you only “know” the language in your head but never speak it, the skill becomes fragile.

- Cognitive: switching, inhibition, and staying focused when two language systems compete.

- Social: belonging, empathy, and stronger cross-cultural relationships.

- Career: clearer customer communication, better service delivery, and access to multilingual roles.

Enhanced mental flexibility

When you manage two languages, your brain practices selecting the right words while ignoring the wrong ones. That is one reason researchers often connect bilingualism with executive control, the set of skills that helps you shift tasks and stay on track.

Evidence is mixed on how big the “bilingual advantage” is across all ages and tasks. Still, the way you practice can make the benefits more likely: you want real use, real time pressure, and real switching.

A 2026 Bayesian meta-analysis published in a cognitive aging journal found bilinguals were, on average, about 3.45 years older than monolinguals at dementia symptom onset, while the available incidence studies did not show a clear prevention effect.

Switching languages trains the mind to shift and focus, like exercise for the brain.

- Do weekly “topic swaps”: explain the same work concept once in each language.

- Practice retrieval, not recognition: speak first, then check your bilingual dictionary after.

- Add time pressure: set a 60-second timer and summarize a news story or meeting note out loud.

- Build a repair habit: practice three ways to say the same idea so you can keep going when a word is missing.

Improved cultural understanding

Bilingual education and community language learning do more than teach vocabulary. They give you cultural access, like knowing how to soften a request, show respect, or signal closeness without sounding unnatural.

You can see this in many U.S. cities where schools, courts, and public meetings use bilingual materials. When you can switch comfortably, you become a bridge in a way monolingual communication cannot match.

- Build cultural listening: watch one show or listen to one podcast episode per week in your second language, then summarize it to a friend.

- Choose one community lane: volunteering, professional networking, or parent groups, then commit to showing up in that language.

- Track cultural identity wins: write down moments where language helped you belong, advocate, or reconnect with family.

- Use a bilingual dictionary for tone: look for labels like formal, informal, slang, or regional before you borrow a phrase.

Conclusion

True bilingualism means you can use two languages with ease in the situations that matter, even if you do not feel “perfect” all the time.

In a bilingual community, fluency is a practice, not a status badge.

People become bilingual through family life, bilingual education, and persistent second language use at work and in real relationships. A bilingual dictionary supports that growth best when you use it for part of speech, usage, and IPA pronunciation clues, not just quick translations.

Protect your mother tongue, build routines for your weaker language, and keep showing up for real conversations.

FAQs

1. What does it mean to be bilingual?

Being bilingual means you can use two languages to speak, read, write, or listen. You might be stronger in one language, and skills can change with use.

2. How do I know if I am truly fluent?

True fluency means you can handle real tasks in the other language, like work, school, or casual talk. It does not mean a perfect accent; it means you communicate clearly and understand fast.

3. Does being bilingual mean you must live in a bilingual community?

No, you can be bilingual without living in a bilingual community. A bilingual community helps keep skills strong, but you can learn and use another language at home, online, or at school.

4. How can I grow toward true fluency?

Use the language every day, speak with others, read short texts, and write a little. Set small goals, get feedback, and practice real tasks to build steady progress.