Are Bilingual Toddlers Late Talkers? What’s Normal & What’s Not

You know how quickly language development worries can spike when your toddler hears two languages, understands a lot, but says less than you expected.

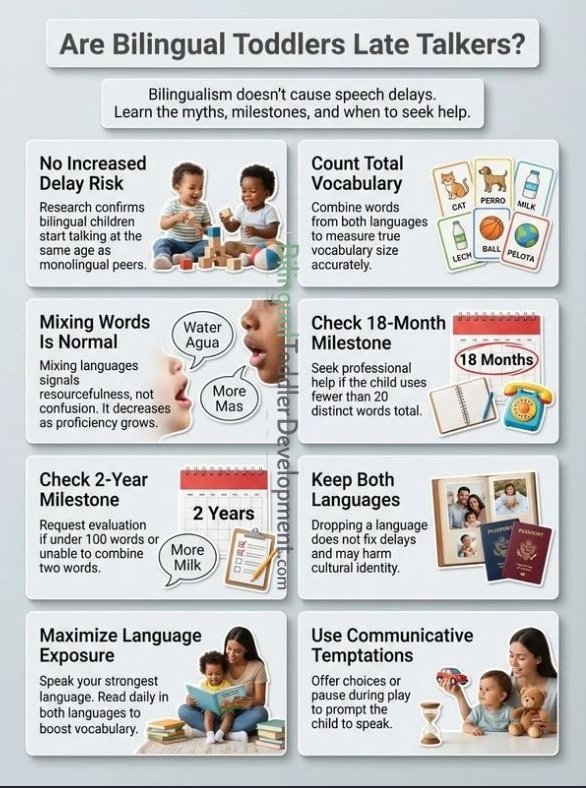

With bilingual children, the most common “late talker” illusion is simple: they split words across a heritage language and a second language, so each language can look smaller on its own.

The reassuring part is that bilingualism itself does not cause language delay.

Below, I’ll show you how to track progress across multiple languages, what code switch and simultaneous bilingualism really look like at home, and the clear signs that mean it’s time to talk with a speech-language pathologist or early intervention.

Key Takeaways

- Bilingualism does not increase the risk of language delays. What changes is how vocabulary is distributed across languages, not a child’s ability to learn language.

- Track total vocabulary across both languages (plus consistent signs or sound-words your child uses on purpose), instead of counting only one language.

- Use practical checkpoints: by 18 months, most toddlers try to say 3+ words besides “mama” or “dada”; by 24 months, most toddlers combine two words (milestones published by the CDC in 2025).

- The Hanen Centre’s parent guidance flags a concern at 24 months when a toddler has fewer than about 50-75 words and is not combining two original words.

- The American Speech-Language-Hearing Association estimates late language emergence in 2-year-olds is often in the 10%-20% range, and many children catch up, but early support helps you avoid months of uncertainty.

- For bilingual or multilingual children, assessment and speech therapy work best when clinicians consider both languages, rather than asking you to drop one language.

Do Bilingual Toddlers Speak Later Than Monolingual Toddlers?

In day-to-day life, bilingual toddlers can look like late talkers because their words are split across two systems. One language might be mostly “home words” and the other might be “child care words.”

But when you add the words together, many bilingual children land right where you’d expect for their age. A 2024 paper in the Journal of Child Language reviewed early milestones (like first words and early word combinations) and found bilingual children reach these milestones at similar ages to monolingual peers.

Here’s the part that helps you make better decisions: you do not need a toddler to have the same number of words in each language. You want to see steady growth in total communication.

How to count words in a bilingual toddler (so you do not undercount)

- Count words in either language. “Milk” and “leche” both count as real words if your child uses them on purpose.

- Count consistent word approximations. If “nana” always means “banana,” count it.

- Count meaningful sound-words. Animal and vehicle sounds can count at this age if your child uses them intentionally (for example, “woof,” “vroom”).

- Do not subtract “duplicates.” Many clinicians use total vocabulary because it tracks growth well in bilingual toddlers, even when words overlap across languages.

For clinical decision-making, SLPs often look at total vocabulary and functional communication (gestures, turn-taking, pointing, showing, requesting). In a 2013 study of Spanish-English toddlers, researchers found total vocabulary growth looked similar to monolingual growth when measured this way, which supports why clinicians ask you to count both languages during early screening.

A key rule of thumb: if a child has a true language disorder, it tends to show up across languages, not only in the newer language.

If your child truly has a language delay or developmental language disorder, you can still raise them bilingually. The American Speech-Language-Hearing Association states that using multiple languages does not confuse children or cause speech or language problems, and that a strong foundation in one language supports additional language learning.

Normal Language Development in Bilingual Toddlers

Most bilingual toddlers move through the same stages as monolingual toddlers. They babble, use first words, and start combining words, just spread across two languages.

What helps most is not drilling flashcards. It is steady, responsive interaction in routines you already do: meals, bath, dressing, play, and book time.

If you want a U.S.-based reference point, the CDC’s milestone checklists (updated in 2025) are a practical way to sanity-check language development without turning your home into a testing center.

A simple “two-language” milestone snapshot

| Age | What to look for (across both languages) | What you can do this week |

|---|---|---|

| 18 months | Tries to say 3+ words besides “mama” or “dada,” and follows one-step directions (CDC) | Offer choices (“milk or water?”), then pause and wait for a response |

| 24 months | Says at least two words together (CDC). The Hanen Centre flags concern if fewer than about 50-75 total words and not combining two original words. | Model two-word phrases that fit your routine (“more grapes,” “open box”) |

| 3 years | Longer phrases, more verbs and adjectives, and clearer speech. If progress stalls for months, get support. | Use play to practice action words (“jump,” “pour,” “push”), not just labels |

One more practical point: toddlers learn best from back-and-forth interaction, not passive listening. The CDC’s guidance for 18-month-olds also emphasizes limiting screen time, with video calling as an exception for young toddlers, which can be a helpful way to connect with relatives in a heritage language.

Developmental milestones for bilingual children

Bilingual toddlers follow the same core milestones as monolingual peers, but you measure them across two languages. If you want to be systematic, ask an SLP about parent checklists like the MacArthur-Bates Communicative Development Inventories, which are widely used in research and clinical tracking.

- 12 months: You often see intentional communication through babble, gestures (like reaching), and a few meaningful words. If there is no babbling, pointing, or response to name, bring it up with your pediatrician.

- 18 months: Many toddlers try 3+ words besides “mama” or “dada,” and follow one-step directions (CDC). If your child has far fewer attempts and also struggles to understand simple directions, you should get guidance sooner rather than later.

- 24 months: Many toddlers use two-word combinations (CDC). The Hanen Centre recommends extra support when a child is not combining two original words and has a very small vocabulary for age (often described around 50-75 total words at 24 months).

- 24-30 months: Watch for growth in word types, not just more nouns. You want to hear more verbs (“go,” “want”), adjectives (“big,” “hot”), and early prepositions (“in,” “on”).

- 3 years: You should hear more sentence-like speech and see your child using language to tell you what happened, ask questions, and negotiate during play. If you feel like your child is stuck at single words for a long stretch, it is worth an evaluation.

Differences between monolingual and bilingual language acquisition

Monolingual toddlers build one vocabulary bank. Bilingual or multilingual toddlers build two, and the amount of exposure to each language affects how quickly each bank grows.

That is why you can see “lags” in one language that are not clinically meaningful, especially right after a big routine change (starting child care, a new caregiver, a move). What matters is whether your child keeps building language skills somewhere, and whether they can use communication to get needs met.

Simultaneous vs sequential bilingualism (and what it means for you)

| Type | What it usually means | What you might notice | How to support it |

|---|---|---|---|

| Simultaneous bilingualism | Exposure to two languages from birth or in the first few years | Words appear in both languages, sometimes mixed in one sentence | Stay consistent, respond to the message, and model the phrase naturally |

| Sequential bilingualism | A second language becomes strong after the first language is already established | Fast growth in the “new” environment language over time, with stronger home vocabulary in the heritage language | Keep the home language rich, and give meaningful chances to use the second language socially |

Code switch vs confusion: what’s normal

- Code switch (or code mixing) is when a child uses both languages in a sentence or conversation. The American Speech-Language-Hearing Association describes this as a normal part of learning and using more than one language.

- Switching often drops as children gain more vocabulary in both languages, especially once they learn which language “works best” with which person.

- If you want a clean way to respond, repeat your child’s message back in a simple model in the language you were using, without demanding they repeat it.

Common Myths About Bilingualism and Speech Delays

Parents hear a lot of confident advice about bilingualism. Some of it is well-meaning, and some of it pushes families to drop a language too quickly.

Use this section as a filter: what is normal, what is a myth, and what should trigger a real evaluation.

Does bilingualism cause confusion?

No. Mixing words from two languages is not the same as confusion. It is a communication strategy, and it often shows your child is motivated to get a message across.

The American Speech-Language-Hearing Association explicitly notes that mixing grammar rules or words across languages can happen, and that it is a normal part of using more than one language.

Research also supports why this is not automatically a problem: a well-known 2014 study on code-switching in speech to toddlers found no evidence that caregiver code-switching delayed word learning.

Children use every tool they have to talk.

What to do if your toddler mixes languages in the same sentence

- Respond to the meaning first. Treat it like successful communication.

- Model a short, clean version. “Sí, more milk” can become “More milk” (or the equivalent in your heritage language) in your response.

- Keep your tone warm. Pressure can reduce attempts, especially in toddlers who are already cautious talkers.

Can bilingualism lead to speech delays?

Bilingualism does not increase the risk of language delay by itself. A bilingual child can still be a late talker, but the bilingualism is not the cause.

Where families get stuck is mistaking “distributed exposure” for a disorder. If your toddler has strong gestures, understands a lot, engages socially, and keeps adding words, you are likely seeing a normal bilingual pathway.

If a child has a true language delay, clinicians expect to see concerns across the child’s communication system, and in more than one setting. That is when an SLP can help you sort out whether you are seeing a temporary lag, a late talker profile, a speech delay (speech sounds), or a broader language disorder.

When to Seek a Speech-Language Evaluation

If you are debating whether to “wait a little longer,” here is the line I use with families: do not wait through a period where you are seeing no new skills. You want forward motion, even if it is slow.

A 2023 clinical review published by the American Academy of Family Physicians advises that watchful waiting is not recommended for late talkers who have fewer than 50 words at 24 months or who are not combining words, and it recommends starting with speech-language pathology and audiology evaluation when concerns are present.

What a good bilingual evaluation looks like

- A detailed parent interview about language exposure (who speaks what, and when)

- Measures of understanding and expression, not just “how many words”

- Sampling communication in ways that fit your child (play-based, routines, interaction)

- Consideration of both languages, often with an interpreter if needed

- Clear next steps you can do at home, even while you are waiting for services

If you’re in the U.S., here’s the fastest path to help

- Book an SLP evaluation and ask if they routinely assess bilingual or multilingual children.

- Request a hearing check. The Hanen Centre recommends hearing evaluation for late talkers, even when hearing seems fine day to day.

- Call your state’s early intervention program if your child is under 3. The CDC notes you can refer your child yourself, and many programs provide services free or at reduced cost if eligible.

- Know the timeline. Under federal Part C rules, states generally follow a 45-day timeline from referral to evaluation and an initial plan meeting, with limited exceptions.

- If your child is 3 or older, contact your local public school system to request an evaluation for preschool special education services (the CDC describes this as the next step after age 3).

Signs of true language delay

Bilingual children can have uneven strengths across languages, so you do not want to panic about one-language counts. Instead, watch for patterns that suggest a broader problem.

- 12 months: Limited or absent babble, minimal gestures (pointing, showing), or not responding to name are meaningful concerns to discuss with your pediatrician.

- 18 months: Not trying to say 3+ words besides “mama” or “dada,” or not following simple one-step directions (CDC).

- 24 months: Not combining two words (CDC). The Hanen Centre also flags concern when a toddler has a very small total vocabulary for age (often described around 50-75 words at 24 months) and is not creating original two-word combinations.

- Any age: Regression, losing words or social communication skills, needs prompt evaluation.

- Across settings: Your child rarely initiates communication, relies only on pulling you by the hand, or shows little progress even with strong, daily language exposure.

Risk factors to consider

Late talking is common enough that you should not assume the worst, but you also should not dismiss it. The American Speech-Language-Hearing Association estimates late language emergence in 2-year-olds often falls in the 10%-20% range.

- Family history: ASHA notes higher prevalence when there is a positive family history (reported as 23% vs 12% in one cited study set), so share that history during your intake.

- Sex: ASHA reports males are about 3 times more likely than females to show late language emergence, so clinicians often watch boys closely for steady progress.

- Limited gestures: Few points, few shows, limited imitation, and limited pretend play can increase concern.

- Hearing concerns: Frequent ear infections, inconsistent responses, or a “tuned out” pattern should trigger a hearing evaluation.

- Autism screening timeline: In the U.S., the American Academy of Pediatrics recommends autism-specific screening at 18 and 24 months. Screening does not diagnose, but it can speed up the right referrals.

Tips for Supporting Language Development in Bilingual Toddlers

The goal is not to make your toddler “perform.” The goal is to increase the number of easy, low-pressure chances they have to communicate, and to make your responses more helpful.

If you want an evidence-based parent strategy that is simple and effective, the Hanen Centre teaches Observe, Wait and Listen (OWL), including waiting up to 10 seconds to give your child time to start the interaction.

A quick home checklist that supports both languages

- Follow your child’s lead. Talk about what they are already focused on.

- Use short phrases with repetition. You can repeat the key word without turning it into a quiz.

- Build in pauses. After you model, pause and look expectant, so your child has a reason to try.

- Keep screens from replacing conversation. Prioritize real interaction. Use video calls intentionally for relatives in the heritage language.

Encouraging exposure to both languages

Speak to your child in the language you use best. Quality matters, and comfort helps you stay consistent.

ASHA’s public guidance is clear that you will not confuse your child or slow learning by using your languages, and that maintaining a strong foundation in one language supports future learning.

- Choose a realistic structure. One-parent-one-language can work for some families, but a “time and place” routine (home language at home, community language at child care) can be just as effective if you stay consistent.

- Protect the heritage language. Use it for the routines you do most (meals, bath, bedtime), so it stays tied to real life.

- Read daily in both languages. Use board books, library story times, and simple picture books you enjoy rereading. Repetition is a feature, not a flaw.

- Use video calls as language time. A short, frequent call with a grandparent often beats a long, occasional call for keeping a heritage language active.

- Track progress without pressure. Keep a simple note of new words each week across both languages, and bring it to your SLP if you have parent concerns.

- Do not drop a language to “fix” a delay. If therapy is needed, many clinicians support working in the languages your child uses, because language is tied to relationships and cultural identity.

Using interactive activities to support vocabulary

Toddlers learn words fastest when a word solves a real problem for them. That is why play works so well for vocabulary development.

- Use choices. “Apple or crackers?” then pause. A one-word answer is a win.

- Create “missing piece” moments. Put the bubbles out of reach so your child has a reason to request “bubbles” or “more.”

- Imitate, then add one word. If your child pushes a car, you can say “car,” then “fast car,” or “go car.”

- Use expansions. If your child says “dog,” you say “big dog” or “dog run,” in the same language you were using.

- Accept any attempt. If your child tries, respond like it counted, then model the clearer version.

- Practice verbs and prepositions in motion. “In,” “out,” “up,” “down,” “open,” “close,” and “help” show up in daily routines and build useful phrases quickly.

Mini-script: what to say in the moment

| Situation | Your child says | You can model |

|---|---|---|

| Snack | “More” | “More crackers.” |

| Blocks | “Up” | “Blocks up. Up high.” |

| Toys out of reach | Points | “You want the ball. Ball, please.” |

Conclusion

Most bilingual toddlers are not true late talkers. They may speak a little later, or code switch while learning two systems, and that can be completely typical.

When you track total vocabulary and day-to-day communication, you usually get a clearer picture of language development than you do by counting one language alone.

If red flags show up, or progress has stalled, a speech-language pathologist can evaluate both languages, check for a real language delay, and help you access early intervention. Keep your heritage language in the plan, because relationships and culture are part of communication, too.

FAQs

1. Are bilingual toddlers late talkers?

No, bilingual children and multilingual children are not usually late talkers. Total language development, counting both languages, often matches monolingual peers, so it is not always a sign of language delay.

2. How can parents spot true language delays?

Watch for little or no natural communication, very low word repetition, or if delays show up in both languages. If parent concerns remain, seek early intervention and a speech-language pathologist.

3. What can I do at home to help?

Give steady language exposure, read, name things, and use baby talk to keep attention and build words. Use clear phrases, avoid forcing translation, and remember idioms come later.

4. When should I get speech therapy?

Get speech therapy if your child shows clear language delays across both languages, or if they do not join words by the expected age. Early intervention helps most.

5. Where can I find resources and support?

Look for books on amazon.co.uk or amazon.de, join local parent groups, and read trusted guides before you act. Always confirm concerns with a speech-language pathologist.